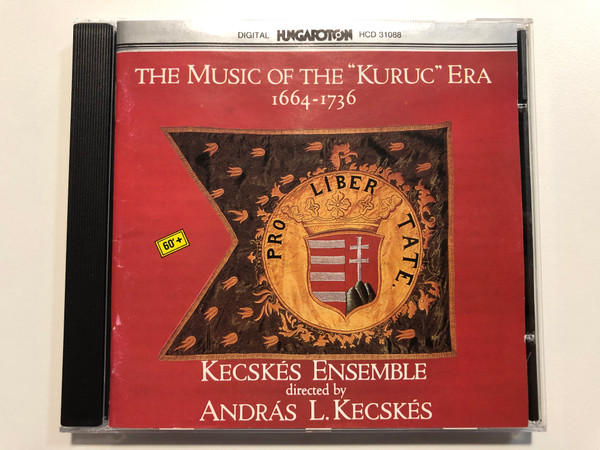

Product Overview

The Music of the "Kuruc" Era 1664-1736 / Kecskés Ensemble - Conducted by András L. Kecskés / Hungaroton Audio CD 1990 / A kuruc kor zeneköltészete

EAN / UPC 5991813108821

HCD 31088

MADE IN HUNGARY

TOTAL TIME: 62:06

!!! Condition of CD is Used Like New !!!

Kuruc (Hungarian: [ˈkurut͡s], plural kurucok), also spelled kurutz, refers to a group of armed anti-Habsburg insurgents in the Kingdom of Hungary between 1671 and 1711.

The kuruc army was composed mostly of impoverished lower Hungarian nobility and serfs, including Hungarian Protestant peasants and Slavs. They managed to conquer large parts of Hungary in several uprisings from Transylvania before they were defeated by Habsburg imperial troops.

The word kuruc was first used in 1514 for the armed peasants led by György Dózsa.[7][8] 18th-century scholar Matthias Bel supposed that the word was derived from the Latin word "cruciatus" (crusader), ultimately from "crux" (cross), and that Dózsa's followers were called "crusaders" because the peasant rebellion started as an official crusade against the Ottomans. Silahdar Findiklili Mehmed Agha, a 17th-century Ottoman chronicler, supposed that the word Kuruc ("Kurs" as it was transliterated into Ottoman Turkish in his chronicle) was a Greek word meaning "polished" or "cilâlı" in Turkish.

Today's etymologists do not accept Bel's or Agha's theory and consider that the word was derived from the Turkish word kurudsch (rebel or insurgent).

In 1671, the name was used by Meni, the beglerbeg pasha of Eger in what is now Hungary, to denote the predominantly-noble refugees from Royal Hungary. The name quickly became popular and was used from 1671 to 1711 in texts written in Hungarian, Slovak and Turkish to denote the rebels of Royal Hungary and northern Transylvania, fighting against the Habsburgs and their policies.

The rebels of the first kuruc uprising called themselves bújdosók (fugitives), or in long form, "different fugitive orders—barons, nobles, cavalry and infantry soldiers—who fight for the material and spiritual liberty of the Hungarian motherland." The army mustered by the northern Hungarian noble Emeric Thököly was also called kuruc. Their uprising forced the Habsburg emperor Leopold I to restore the constitution in 1681 after it was suspended in 1673.

The leader of the last of the kuruc rebellions, Francis II Rákóczi, did not use the term, instead using the French word insurgents or malcontents to highlighting their purposes. Contemporary sources also preferred the term "malcontents" to denote the rebels.

Kuruc was used in Slovakian popular poetry until the 19th century. The opposite term (widespread after 1678) was "labanc" (from the Hungarian word "lobonc," literally "long hair," referring to the wigs worn by the Austrian soldiers), denoting Austrians and their loyalist supporters.

KECSKÉS EGYÜTTES / KECSKÉS ENSEMBLE

László Herczeg — ütőhangszerek / percussion; doromb / Jew:s harp; mandolin

András L. Kecskés — ének / voice; lant / lute: koboz / kobsa; duf: gadulka |

József Kisvarga — ének / voice; hegedű / fiddle: lant / lute; rebek / rebec; fidula / fiddle

Anna Nagy Bartha — ének / voice; viola da gamba: apacahegedu / tromba marina

istván Szabó — theorba, töröksíp / folk shawm; koboz / kobsa -

istván Tóth — ének / voice; zergekürt / gemshorn; furulya / recorder; tábori síp / military flute

Közreműködik / With

Judit Mártha — szoprán / soprano

László Kuncz — bariton / baritone

Istvan Praczky — férfialt / countertenor

András Szabó — ének és próza / reciter

Tünde Kiss — barokk hárfa / barogue harp

Anna Fekete — barokk furulya / recorder

Eniké Boros — barokk oboa / baroque oboe

Péter Léval — barokk furulya / recorder, gorbekirt / crumhorn: tordksip / folk shawm

Réka Kürthy — hegedű / violin

Balázs Nagy — ének / voice; tekerőlant / hurdy-gurdy

Reneszánsz Harsona Együttes

The Renaissance Sackbuts

(László Arató, Tamás Gruber, Zoltán Hidegkúti, Imre Vass, József Vágó)

Kamarakórus / Chamber Choir

(Karigazgaté / Chorus master: Gabor Szabó)

Művészeti vezető / Directed by

ANDRÁS L. KECSKÉS

Tracklist

1 Zsigmond Petko’s Song (c.1660; Balassa Codex)

2 Song on Miklés Zrinyi (after M. Zimmermann, Augsburg 1664)

3 Song of an Outlaw (Andras Janéczi?)

4 Song of an Outlaw (Alia, Vietorisz Codex)

5 Song of Jakab Buga (1688; Szentsei Song Book)

6 L’arrivée du Prince Eugene (c.1700; Jacques de Saint Luc)

7 Leopold | (Head of the Holy Roman Empire and King of Hungary): Guldnes Leben (1683)

8 Thokély’s War Council (1681; Thakély Codex)

9 A Name-day greeting (Ferenc and Julia Rákóczi to their mother, llona Zrinyi, 1686; Thokély Codex)

10 The tune of Imre Thokély’s dance (1689; The Sopron Virginal Book)

11 Cantemir: Pegrev in buzurk scale (c.1700)

12 Istvan Dobai: It was miserable (late 17th century; Szentsei Song Book)

13 Marche du Thekeli (1712; Sr. Dezais)

14 Mary, Mother ot Hungarians (1705—14; Demeter Szoszna’s Song Book)

15 Song on the taxes (1697; Thokély Codex)

16 Song on the death of Captain Lehmann (1703; Szentset Song Book)

17 a) The Proclamation of Ferenc Rak6czi Il (1703)

b) Hungary, Transylvania, hear the news (1705; Mihaly Szolga’s diary)

18 My cap is of Turkish velvet (From Transylvanian tradition)

19 a) Dances from the Kajoni Codex (1634—71)

b) Hajdd Dance from Transylvania (1705; Szentsei Song Book)

20 Hungaricam menuet (1729; The Linus Manuscript)

21 Dawn (c.1680; Vietorisz Codex)

22 a) Musqueteers’ March (known since 1630, military tradition)

b) The Rakéczi Song

23 Csinom Palko (late 17th century; Bocskor Codex)

24 a) Kelemen Mikes: We live at the seashore

b) Dances from the Apponyi Manuscript (1730)

25 Tamas Ujvari: O how wonderful (1705)

26 a) An Epilogue (from the Archives ot the Istambul Serail)

b) Death is a reaper (Janos Kajoni: Cantionale catholicum: 1676)

Dallista:

1 Petkó Zsigmond éneke (1660 k.; Balassa-kódex)

2 Ének Zrinyi Miklósról (M. Zimmermann után, Augsburg, 1664)

3 Szegény legény éneke (Jánóczi András?)

4 Szegény legény éneke (Alia; Vietorisz-kódex)

5 Buga Jakab éneke (1688; Szentsei daloskönyv)

6 Jenő herceg érkezése (Jacgues de Saint Luc, 1700K.)

7 I. Lipót: Aranyélet (1683)

8 Thököly haditanácsa (1681; Thököly-kódex)

9 Névnapi köszöntő (A Rákóczi-gyermekek Zrinyi Ilonához 1686-ban; a Thököly-kódex)

10 Thököly Imre táncza nótája (1689; Soproni virginálkönyv)

11 Cantemir: Pesrev büzürk hangsorban (1700k.)

12 Dobai István: Siralmas volt nékem (XVII. század második fele; Szentsei daloskönyv) ver"

13 Thőköly-induló (1712; Sr. Dezais)

14 Mária Magyarok Annya (1705—14; Szoszna Demeter énekeskönyve)

15 Ének a porcióról (1697; Thököly-kódex)

16 Ének Lehmann százados haláláról (1703; Szentsei daloskönyv)

17 a) II. Rákóczi Ferenc kiáltványa (1703)

b) Magyarország, Erdély, hallj új hírt (1705; Szolga Mihály diáriuma)

18 Török bársony süvegem (Erdélyi néphagyomány)

19 a) Táncok a Kájoni-kódexből (1634— 71)

b) Erdélyi hajdútánc (1705; Szentsei daloskönyv)

20 Magyar menüett (1729; Linus-féle kézirat)

21 Hajnal (1680 k.: Vietorisz-kódex)

22 a) Muskétások indulója (1630-tól; katonahagyomány)

b) Rákóczi-nóta

23 Csinom Palkó (XVII. század vége, Bocskor-kódex)

24 a) Mikes Kelemen: Lakunk partján a tengernek

b) Táncok az Apponyi-kéziratból (1730)

25 Újvári Tamás: Ó, mely csudálatos (1705)

26 a) Epilógus (Az isztambuli Szeráj levéltárából)

b) Kaszás e földön a halál (Kájoni: Cantionale catholicum, 1676)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)