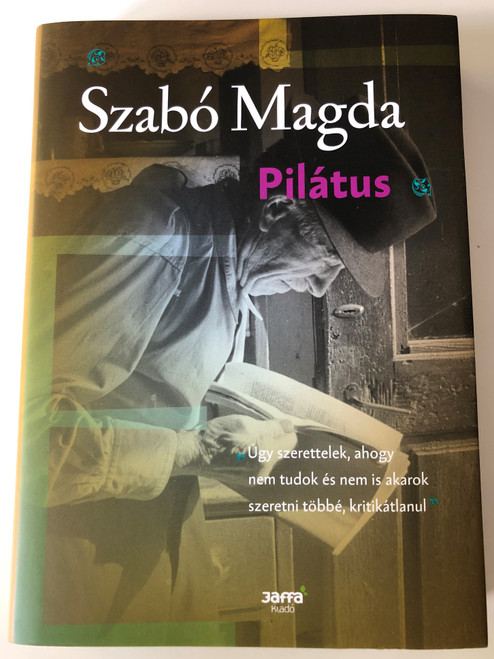

Product Overview

Az ajtó by szabó Magda / The door - Hungarian novel / Jaffa Kiadó 2016 / Hardcover

Hardcover 2016

ISBN: 9786155609053 / 978-6155609053

ISBN-10: 6155609055

PAGES: 281

PUBLISHER: Jaffa Kiadó

LANGUAGE: Hungarian / Magyar

Hungarian Description:

Álmában nem, de életében egyszer kinyílik az ajtó az írónő előtt. Szeredás Emerenc ajtaja, amely mások számára örökre zárva marad. A megingathatatlan jellemű, erkölcséhez és hiedelmeihez tántoríthatatlanul ragaszkodó asszony házvezetőnőnek áll az írónőhöz, ám első perctől nyilvánvaló, hogy ő diktál. Gazdája megmérettetik, és nem találtatván könnyűnek, Emerenc nem csupán otthona, hanem lelke ajtaját is megnyitja előtte, ha csak résnyire is. Így sejlik fel Magyarország huszadik századi történelmének kulisszái előtt egy magára maradt nő tragikus, fordulatos sorsa. Vajon mit őrizget az idős asszony ah ét lakatra zárt ajtó mögött?

Az ajtó a ki- és bezártság, a születés és a halál ősi jelképe. Állandó kettősség jellemzi a két főhős áhítatos odaadó, máskor szinte gyűlölködő kapcsolatát is. A szeretet kapujában állnak. Sikerülhet-e végül beljebb vagy elengedni egymást?

Az ajtó Szabó Magda talán legismertebb regénye: Szabó István forgatott belőle filmet, és 2015-ben felkerült a The New York Times sikerlistájára.

Részlet a könyvből:

Ritkán álmodom. Ha mégis, verejtékben fürödve riadok fel. Ilyenkor visszadőlök, megvárom, míg a szívem megnyugszik, s eltűnődöm az éjszakák kivédhetetlen, mágikus hatalmán. Gyerekként vagy fiatalon nem álmodtam se jót, se rosszat, csak öregség sodorja újra meg újra felém a múlt hordalékából keményre gyúrt iszonyatot, amely azért olyan riasztó, mert feszesebbre komponált, tragikusabb, mint bármikor is átélhettem volna, hiszen a valóságban egyszer sem történt meg velem az, amitől sikoltozva ébredek.

About the Novel

The novel begins with Magda, the narrator, recounting the recurring dream that haunts her in her old age. As Magda explains, after waking up from this dream, she is forced to face the fact that "I killed Emerence". The story that follows is Magda's attempt to explain what she means by this sentence; it is the comprehensive story of her decades-long relationship with her housekeeper Emerence. When the story begins, Magda has just come into favour with the government and her works are finally allowed to be published again. She realises that she must employ a housekeeper to be able to dedicate herself to writing full-time. A former classmate recommends an older woman named Emerence. Emerence agrees to come work for her on her own terms, but she will not, she informs Magda, just be a person to "wash the dirty linen" of whoever is willing to hire her. For several years, Magda and Emerence have a somewhat unconventional relationship. Emerence sets her own wages and her own hours, and even chooses which household chores she will or will not accept. Even though she works in Magda's home, Emerence remains as much an enigma to Magda as she is to the rest of the neighbourhood. The neighbours on their street are bewildered by but still respect this odd elderly woman who is so particular in her habits and guards the closed doors of her house with the utmost secrecy.

Magda Szabó (October 5, 1917 – November 19, 2007) was a Hungarian novelist. She also wrote dramas, essays, studies, memoirs, and poetry. She is the most translated Hungarian author, with publications in 42 countries and over 30 languages.

Szabó began her writing career as a poet and published her first book of poetry, Bárány ("Lamb"), in 1947, which was followed by Vissza az emberig ("Back to the Human") in 1949. In 1949 she was awarded the Baumgarten Prize, which was immediately withdrawn when Szabó was labeled an enemy to the Communist Party. She was dismissed from the Ministry in the same year. The Stalinist era from 1949 to 1956 censored any literature, such as Szabó's work, that did not conform to socialist realism. Since her husband was also censored by the communist regime, she was forced to teach in a Calvinist girls' school until 1959.