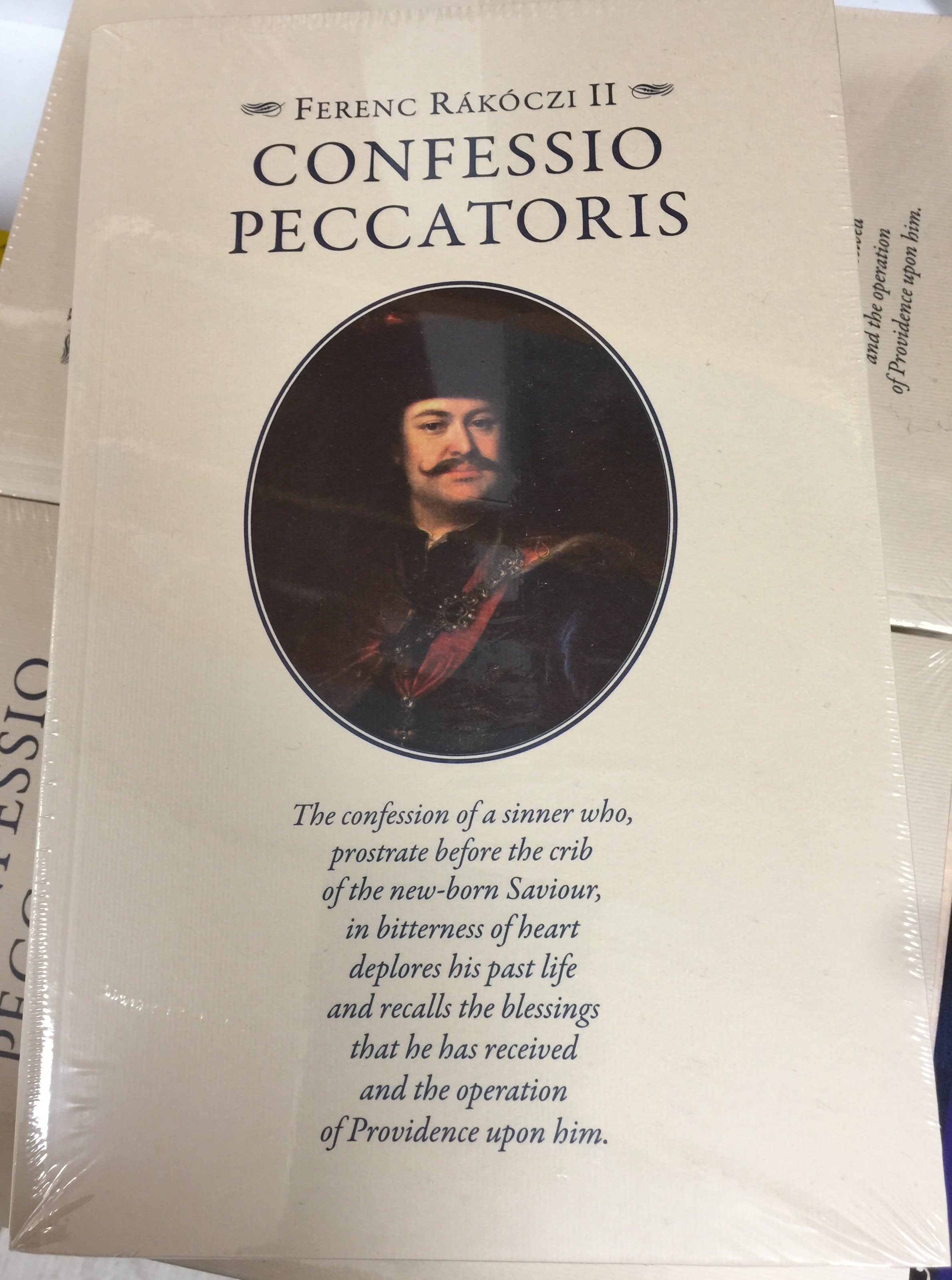

Product Overview

Confessio Peccatoris Vol. I-II by Ferenc Rákóczi II / Vallomások c. mű I. és II. kötet Angol nyelven / The confessions of a sinner / Paperback / Corvina

- PAPERBACK: 2019

- ISBN: 9789631365641 / 9789631365641

- PAGES 628

- PUBLISHER: CORVINA

- Méret / Size: 214 mm x 138

About the Author:

Francis II Rákóczi (Hungarian: II. Rákóczi Ferenc, Hungarian pronunciation: [ˈraːkoːt͡si ˈfɛrɛnt͡s]; 27 March 1676 – 8 April 1735) was a Hungarian nobleman and leader of the Hungarian uprising against the Habsburgs in 1703-11 as the prince (fejedelem) of the Estates Confederated for Liberty of the Kingdom of Hungary. He was also Prince of Transylvania, an Imperial Prince, and a member of the Order of the Golden Fleece. Today he is considered a national hero in Hungary.

Felsővadászi II. Rákóczi Ferenc (Borsi, 1676. március 27. – Rodostó, 1735. április 8.) magyar főnemes, a Rákóczi-szabadságharc vezetője, erdélyi fejedelem, birodalmi herceg (Reichsfürst). 1704-ben Gyulafehérvárott erdélyi fejedelemmé választották, és így ő volt az utolsó, aki betöltötte ezt a tisztséget. 1705-ben a szécsényi országgyűlésen a dux & princeps címeket kapta, amely „vezér és fejedelem” jelentésű, és a magyar történetírás hagyományos értelmezése szerint ezzel megválasztották „a haza szabadságáért összeszövetkezett magyar rendek vezérlő fejedelmévé”.

Neve szorosan összefügg az általa 1703-ban indított Rákóczi-szabadságharccal, melyben a teljes állami függetlenséget kívánta visszaszerezni a Habsburg Birodalomtól. E célnak megfelelően választották Erdély és Magyarország fejedelmévé, aminek tökéletesen megfelelt, mivel Rákóczi Zsigmond erdélyi fejedelem leszármazottja volt, azonkívül dédapja és nagyapja, I. Rákóczi György és II. Rákóczi György, továbbá apja I. Rákóczi Ferenc is erdélyi fejedelem volt.

English Summary:

The English translation by Bernard Adams of the autobiography and memoires of Hungary´s national hero Ferenc Rákóczi II has now been published by Corvina with support from The Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

Confessio peccatoris; we enter the scene as the failure of the 1703-11 war is imminent:

While I was engaged on this my little army grew as the days went by. The nobility of the adjoining counties took my side and sent the poorest noblemen to enquire into the condition of my forces and my intentions. Some pointed out the danger that awaited me if the Austrians sent assassins to kill me, others brought news that the heavy cavalry of the Montecuccoli regiment had arrived in Ungvár. This was confirmed by a nobleman who shortly arrived after travelling with the said regiment for some days. I could therefore not doubt the truth of this information. I considered it, however, a step fraught with very grave consequences suddenly to retreat, with an army which everywhere was believed to have ten times as many men in the field, at the first sound of the approach of a single regiment. That timid move would have dismayed the people and the army alike. On the other hand, I had to believe that it was more dangerous for three thousand foot and five hundred horse, armed at best with peasant fire-arms, to await a regiment of twelve hundred heavy cavalry – and that in a completely exposed place full of thatched wooden houses, so jeopardising to the utmost the safety of my person and the interests of my country.

I was therefore in great need of good advice in order on the one hand to be able to maintain the morale of the men and the good opinion which they had formed of their own strength, and on the other to avoid the imminent danger. Salutary advice I could expect only from myself. I sent out all manner of scouting parties and spies and decided to conceal the news of the approach of the Austrians and in the course of the night to send the completely unarmed part of the army into the hills to the castle of Beregszentmiklós, two miles from the town, on the pretext that on my order they were to go around it through the forest and then return from the back. Thus those in the castle would believe that new forces had arrived. My real purpose, however, was by that ruse to remove the completely unarmed men, that is, the greater part of my force, and then, if I learnt from the scouting parties that I had sent everywhere that the Austrians were approaching, I would have good reason for withdrawing and this combined movement would not seem to the people a retreat caused by fear. I retained a small part of the better armed and then went to bed.

Next day at dawn, just as the sentries of the day had set out to relieve those who, the previous evening, had pulled back to the island in the Latorca next to the town, and had already crossed the water to take up their daytime positions and were establishing look-outs on the high ground, they encountered an enemy squadron which attacked and forced them back. I was at the time dressing in my house, which was undefended and surrounded by a hedge. At the same time I saw the remainder of my cavalry, who were in constant readiness, galloping headlong across the square outside to the defence of the sentries. The small body of infantry that I had retained were in the courtyard of the house, and I had only time to position part of them along the hedge and the rest among the little stalls on the opposite side of the square. I say ‘only time’, because my cavalry returned very quickly with a big squadron on their tail. They rushed past the gate of my house and scattered. The enemy, however, as they pressed forward came between two fires. Majos and I were mounted in the gateway, together with a few cavalry that had remained with me. The gate was open, and when the squadron were passing these latter burst furiously out. Majos flung himself at the captain, who the previous evening had boasted that he would have my heart skewered on his sword. Majos, however, killed him, and another thirty or so were left dead. Thus the squadron went in disarray as far as the cemetery at the end of the town, and there made a stand. In that awkward situation I had no time to lose and had to make a choice: either defence in a thatched house surrounded by a hedge, standing among similar houses, or a no less dangerous retreat from the cavalry, as we lacked the weaponry to beat them back. The majority thought that we must opt for defence. But even if walls had surrounded the house the castle was at readiness to assist with cannon. I therefore decided on retreat.

I encouraged my men and drew them up in column of route without having trained them much in that formation, and in fact they were incapable of keeping their dressing. The Austrians set fire to the houses beyond mine. The wind enveloped everything in smoke, which I turned to our advantage. When, however, I reached the middle of the square the end of the column began to waver and wished to turn back. I halted the front of the column and repeated my encouragement, and we set off once more in full view of the squadron. It, however, did not move, clearly counting on hurling itself upon the rear-guard and then attacking us. I rode in the middle of the column with some fifteen horsemen who were prepared to face whatever came upon us. A private soldier came to me and offered the advice that we should turn towards the river; he knew a shallow place where the infantry could cross easily and reach the hedge of the village of Oroszvég opposite, and from there the vineyards and the forested high hills. After a moment’s hesitation I accepted that advice. The enemy was by then surrounding the town with the intention of burning it, and in addition was awaiting infantry from the castle. They became very confused on seeing us cross the river. Some of the squadron in fact followed us, but by then we had passed through the hedges, from where we reached the vine-hills with ease. At the top I halted my men, and we saw infantry emerging from the castle with field artillery and the Montecuccoli regiment lined up by squadrons in the streets leading to the fields. Thus did the invisible hand of God protect us in the danger. On that occasion I lost my most necessary belongings. All that I had was packed in two bags, but my servant, who was unwell, forgot to stow them on the horse.

...

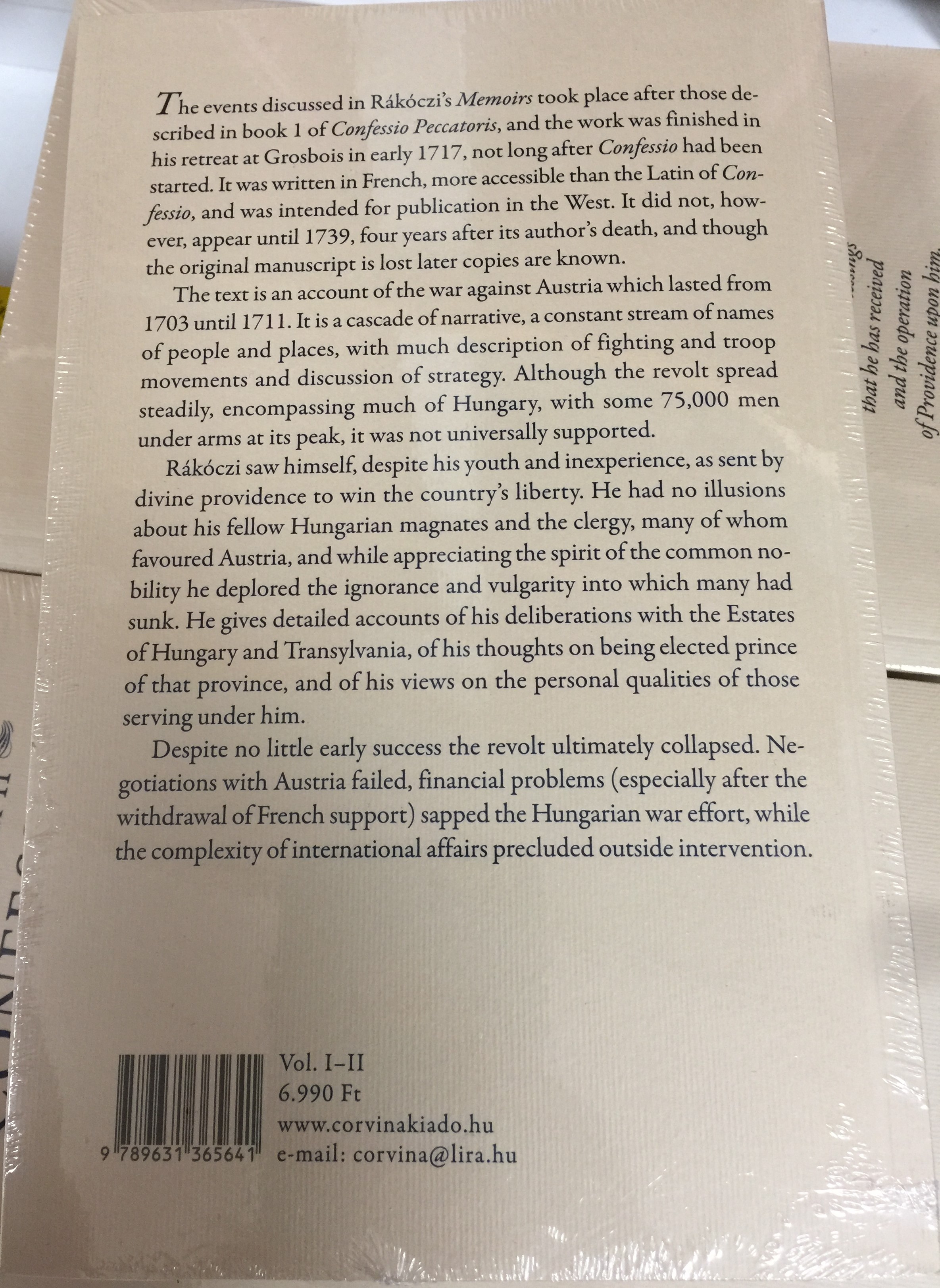

FROM THE BACK COVER:

The events discussed in Rákóczi’s Memoirs took place after those described in book 1 of Confessio Peccatoris, and the work was finished in his retreat at Grosbois in early 1717, not long after Confessio had been started. It was written in French, more accessible than the Latin of Confessio,and was intended for publication in the West. It did not, however, appear until 1739, four years after its author’s death, and though the original manuscript is lost later copies are known. The text is an account of the war against Austria which lasted from 1703 until 1711. It is a cascade of narrative, a constant stream of names of people and places, with much description of fighting and troop movements and discussion of strategy. Although the revolt spread steadily, encompassing much of Hungary, with some 75,000 men under arms at its peak, it was not universally supported. Rákóczi saw himself, despite his youth and inexperience, as sent by divine providence to win the country’s liberty. He had no illusions about his fellow Hungarian magnates and the clergy, many of whom favoured Austria, and while appreciating the spirit of the common nobility he deplored the ignorance and vulgarity into which many had sunk. He gives detailed accounts of his deliberations with the Estates of Hungary and Transylvania, of his thoughts on being elected prince of that province, and of his views on the personal qualities of those serving under him. Despite no little early success the revolt ultimately collapsed. Negotiations with Austria failed, financial problems (especially after the withdrawal of French support) sapped the Hungarian war effort, while the complexity of international affairs precluded outside intervention.

Memoirs, translated by Bernard Adams and an afterword by Gábor Tüskés, will be available early this year from Corvina Press.

Hungarian Summary:

Mikes Kelemen és Szepsi Csombor Márton Corvinánál megjelent emlékiratai után ismét egy különleges történelmi emléket vehet a kezébe az angolul olvasó: az eredetileg latinul írt Confessio (Vallomások) és a franciául írt Mémoires (Emlékezések) köteteit, amelyek együttesen nemcsak Rákóczi hiteles önéletrajzának tekinthetők, hanem a saját korán messze túlmutató történeti, filozófiai, vallási tárgyú értekezésnek, a korszak ,,foglalatának". Angol nyelven most jelenik meg először. Fordította: Bernard Adams. A bevezető tanulmányt Robert Evans, az oxfordi egyetem professzora, a két kísérő tanulmányt pedig Tüskés Gábor irodalomtörténész írta.